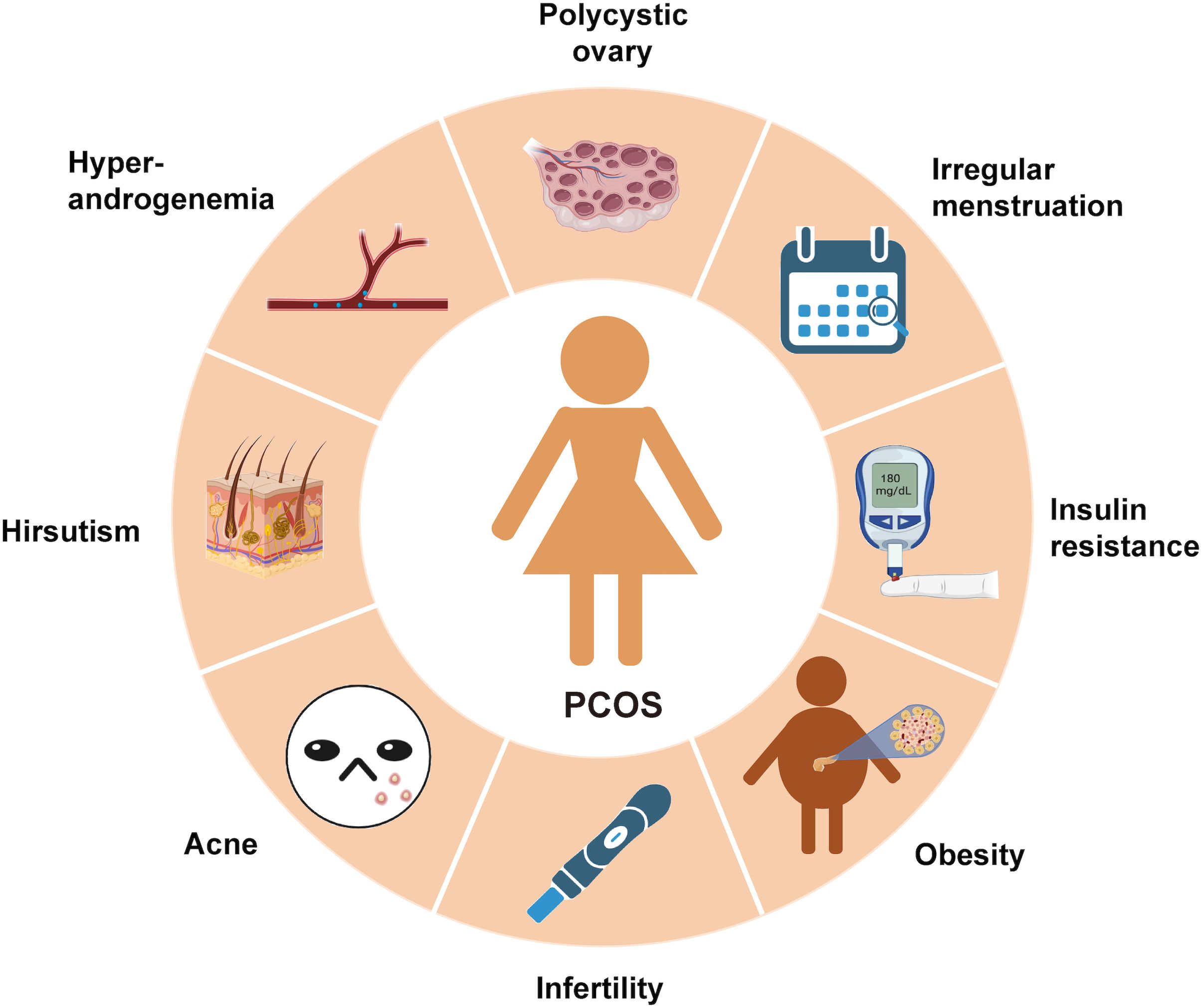

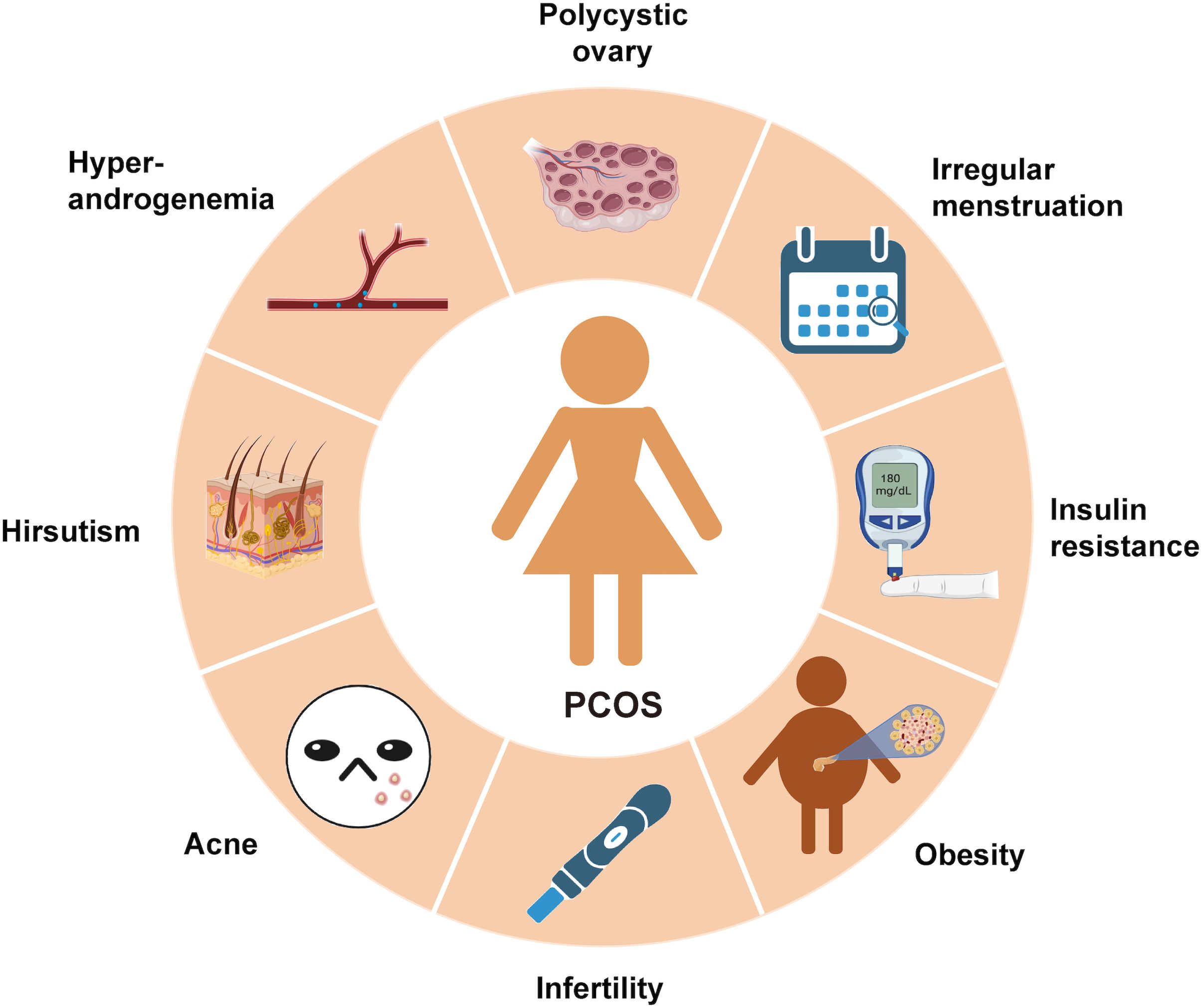

A misleading narrative about Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) has persisted throughout the years. PCOS is primarily diagnosed based on irregular periods, infertility, and polycystic ovaries on ultrasound. The misconception that PCOS is merely a reproductive disorder has prevented millions of women from receiving appropriate care for its metabolic roots. In truth, PCOS is a complex, systemic condition characterized by chronic inflammation, insulin resistance, and endocrine disruption processes that manifest in reproductive symptoms but extend far beyond them. To truly understand PCOS, a step back is required to view the full inflammation-insulin-androgen triangle that underlies this syndrome. ·

PCOS as a Chronic Inflammatory Condition

In recent years, PCOS has been reclassified by many researchers as a low-grade inflammatory disorder (González et al, 2018). Importantly, this inflammation is not merely a consequence of obesity; it is often independent of BMI and is observed even in lean women with PCOS

.

Key findings from the literature include:

• Elevated levels of inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF α) are consistently reported in PCOS cohorts (González et al, 2018).

• Inflammation interferes with insulin signaling by disrupting the insulin receptor substrate (IRS), ultimately impairing glucose uptake (Macut et al., 2017).

• Adipose tissue, particularly visceral fat, functions as a pro-inflammatory endocrine organ, secreting cytokines and further reducing insulin sensitivity.

This state of immune activation often begins early in life and contributes to both the metabolic and ovarian dysfunctions associated with PCOS.

Insulin Resistance: The Unseen Engine of PCOS

While inflammation sets the stage, insulin resistance drives the PCOS cycle forward. Approximately 65-90% of women with PCOS exhibit insulin resistance, depending on phenotype and weight status (Houston & Templeman, 2025). Insulin’s role in PCOS extends well beyond glucose regulation:

• Androgen production: Insulin directly stimulates ovarian theca cells to produce testosterone.

• Testosterone bioavailability: Insulin suppresses hepatic production of sex hormone–binding globulin, increasing circulating free testosterone levels.

Emerging research suggests that hyperinsulinemia may precede insulin resistance in certain individuals, reshaping current models of PCOS pathogenesis (Houston & Templeman, 2025).

The Vicious Metabolic Cycle of PCOS

Linking Inflammation, Insulin Resistance, and Androgens: The inflammation insulin androgen axis forms a self-perpetuating vicious cycle. Pro-inflammatory cytokines impair insulin action; insulin enhances androgen synthesis; and androgens, in turn, exacerbate both inflammation and insulin resistance. This loop ultimately disrupts ovulation, producing the reproductive manifestations of PCOS.

Over time, this chronic metabolic dysfunction increases the risk of long-term complications such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease conditions, not traditionally associated with gynecology but deeply rooted in metabolic pathology (Macut et al., 2017; González et al, 2018).

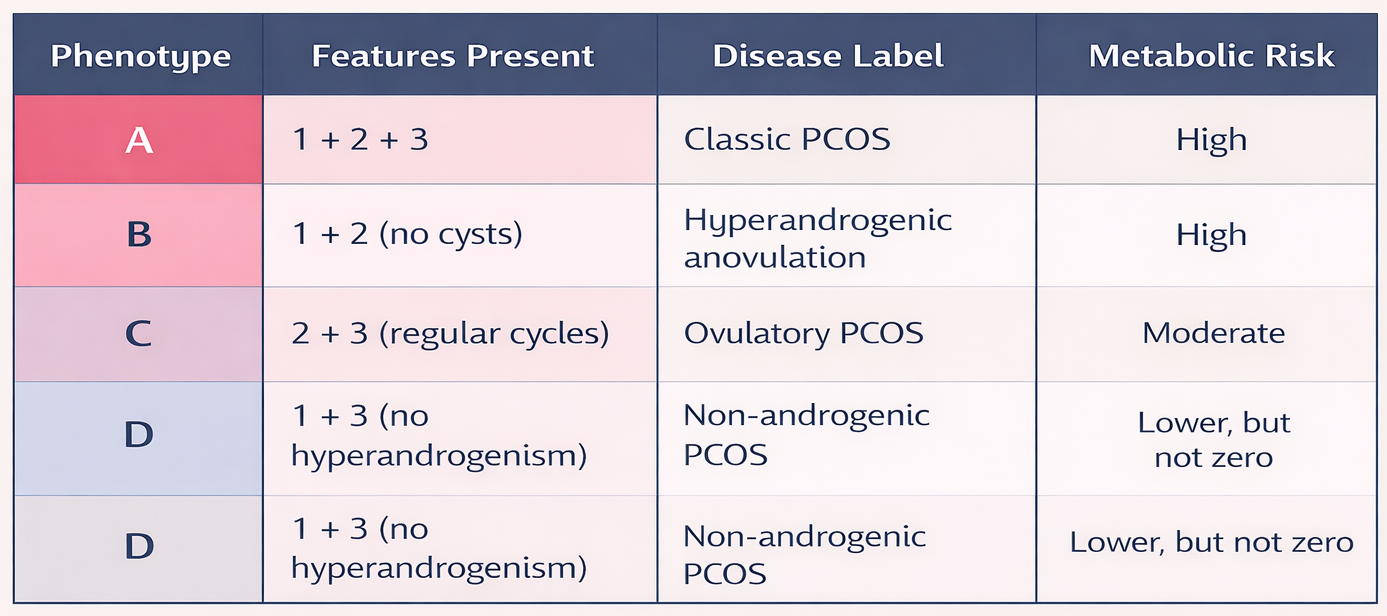

A Closer Look at PCOS Subtypes and Metabolic Risk

According to the Rotterdam criteria, PCOS is diagnosed when at least two of the following features are present (Houston & Templeman, 2025):

1. Ovulatory dysfunction

2. Hyperandrogenism

3. Polycystic ovarian morphology

Based on these criteria, PCOS is classified into four phenotypes:

This classification underscores an important clinical reality: absence of overt reproductive symptoms does not imply metabolic safety. Consequently, screening for insulin resistance and inflammation should be standard practice in PCOS assessment.

Why This Reframing of PCOS Is Critical for Nutrition Practice

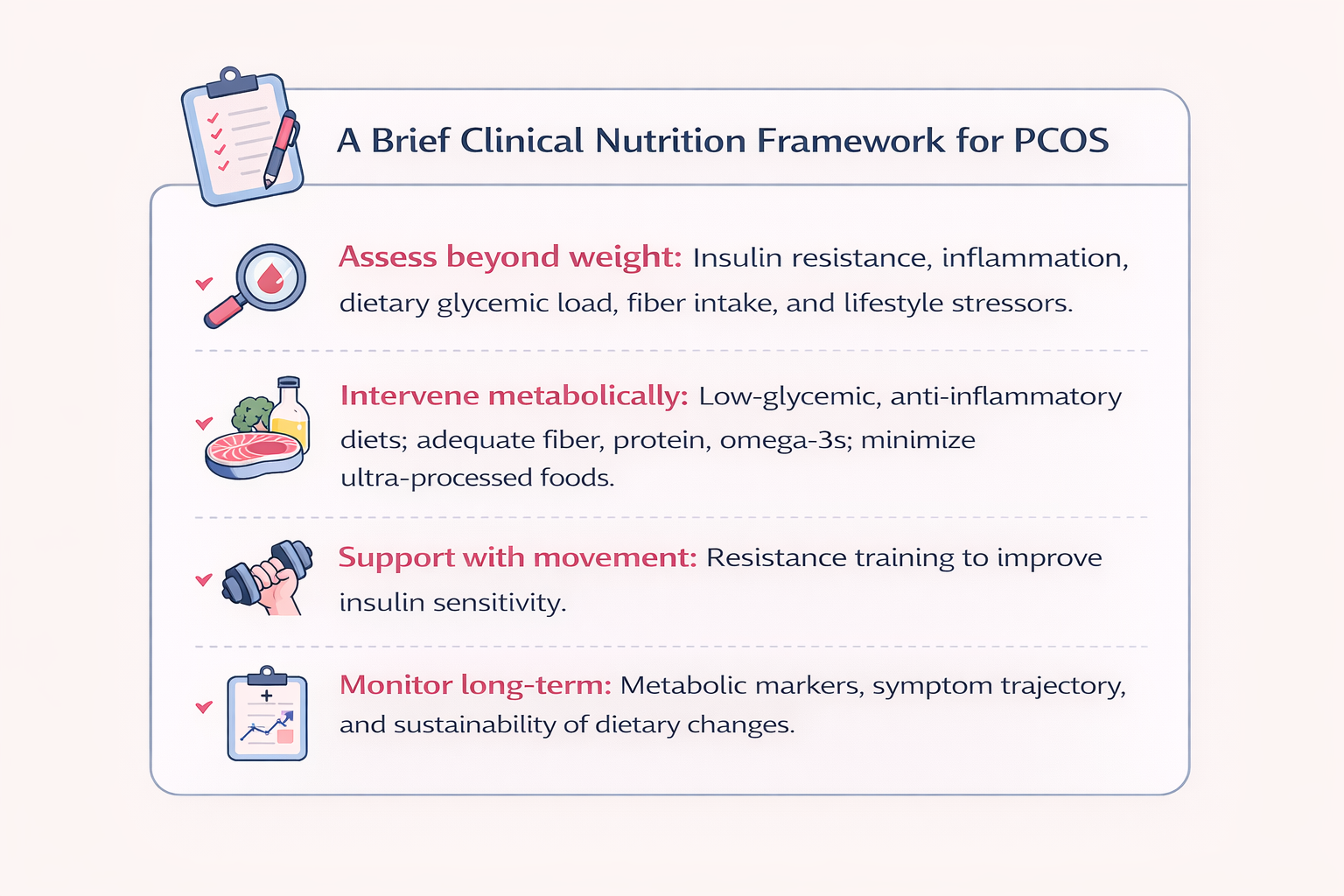

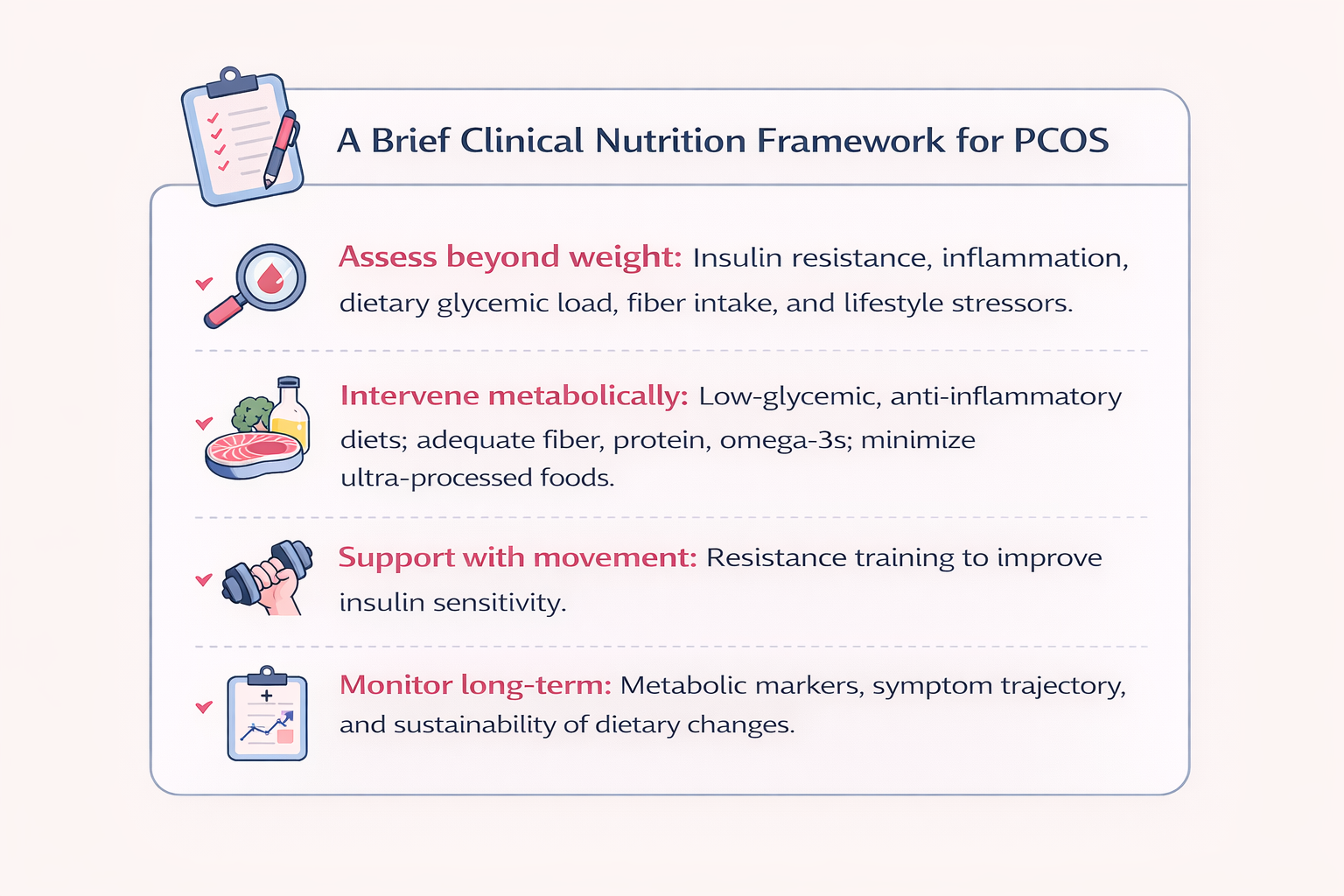

For dietitians and nutritionists, this reconceptualization of PCOS is transformative.

If PCOS is understood primarily as a reproductive disorder, nutrition intervention is often delayed, minimized, or framed only around weight loss. However, when PCOS is recognized as a metabolic–inflammatory condition, nutrition becomes a primary therapeutic tool rather than an adjunct.

Dietitians are uniquely positioned to:

• Identify early metabolic dysfunction in lean and non-obese women with PCOS who may otherwise be overlooked.

• Address chronic low-grade inflammation through dietary patterns rather than symptom-focused restriction.

• Intervene at the level of insulin signaling, which precedes and amplifies hormonal disruption.

This shifts nutrition care from reactive symptom management to preventive metabolic modulation.

Breaking the Cycle: Targeting Inflammation and Insulin

Addressing inflammation and insulin resistance together, rather than focusing solely on androgens or ovulation, offers a more comprehensive and effective approach to PCOS management.

Low-glycemic, anti-inflammatory dietary patterns rich in dietary fiber, omega-3 fatty acids, and plant polyphenols have been shown to reduce systemic inflammation and improve insulin sensitivity (Macut et al., 2017).

Exercise, particularly resistance training, activates insulin-independent glucose uptake pathways in skeletal muscle, complementing dietary strategies. Individualized medical, nutritional, and holistic interventions are therefore essential.

Nutrition as a Long-Term Risk Modifier in PCOS

Beyond symptom relief, nutrition plays a crucial role in modifying the long-term disease trajectory of PCOS.

Sustained dietary strategies can reduce progression toward type 2 diabetes and NAFLD, improve lipid profiles and cardiovascular risk markers, modulate androgen excess indirectly via improved insulin dynamics, and support gut health, which may further influence systemic inflammation

For nutrition professionals, this reinforces the need for long-term, phenotype-specific nutrition planning, rather than short-term dietary prescriptions.

A New Paradigm for PCOS

It is time to shift the narrative. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome is not a disorder of the ovaries—it is a disorder that happens to affect the ovaries.

Preventing and treating inflammation and insulin dysfunction must therefore become the primary objective of care.

PCOS is metabolic.

PCOS is inflammatory.

And yes, PCOS is reproductive, too. But that is only part of the story

References :

• González, F. (2018). Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), an inflammatory, systemic, lifestyle endocrinopathy. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 182, 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2018.04.008

• Houston, E. J., & Templeman, N. M. (2025). Reappraising the relationship between hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance in PCOS. Journal of Endocrinology, 265, e240269. https://doi.org/10.1530/JOE-24-0269

• Macut, D., Bjekić-Macut, J., Rahelić, D., & Doknić, M. (2017). Insulin and the polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 130, 163–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2017.06.011

• Recent Advances in Emerging PCOS Therapies. (2023). Current Opinion in Pharmacology, 68, 102345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coph.2022.102345